Currently reading

Eleven

A Month in the Country

A Tale of the Dispossessed: A Novel

Mesabi Pioneers

The Crusades Through Arab Eyes

Island of a Thousand Mirrors

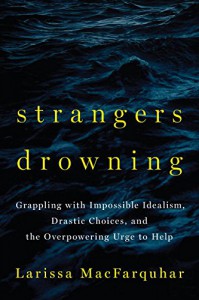

Strangers Drowning: Grappling with Impossible Idealism, Drastic Choices, and the Overpowering Urge to Help

MacFarquhar approaches the subject of extremely ethical people (do-gooders) with the eye of a sociologist. What makes these people tick? How do they question themselves and others? How do they stay sane? These are the folks who question every dollar they spend because it could otherwise pay for medicine for a sick child somewhere in Africa. Who live in dangerous settings for the opportunity to help people, to do some good, to relieve suffering (of people, mostly, but also some chickens).

MacFarquhar approaches the subject of extremely ethical people (do-gooders) with the eye of a sociologist. What makes these people tick? How do they question themselves and others? How do they stay sane? These are the folks who question every dollar they spend because it could otherwise pay for medicine for a sick child somewhere in Africa. Who live in dangerous settings for the opportunity to help people, to do some good, to relieve suffering (of people, mostly, but also some chickens). The title comes from the hypothetical question of whether, when given the chance to save a drowning person who we love (say, your mother) or two strangers, which would you choose? I hate these hypotheticals. If I have time to save two people, one of them should be my mother, and then she can help save the other stranger. Let's work together here. I object to these hypothetical black and white questions. But getting past my issues... The point is that MacFarquhar summarizes the ethics of do-gooders by those who would save the drowning strangers, those who value a life unconnected to them just as much as a loved one, who can detach and see one life vs two and choose the two. This has very real consequences in their personal lives. They do great work, but often don't have great personal lives, since most of us would like to think that someone who loves us would save our lives over those of strangers.

Another characterization that runs throughout the book is that we think these people are crazy in peacetime, but in wartime (the kind of war that actually affects the personal lives of citizens), we all expect personal sacrifice. It's a special case. For do-gooders, MacFarquhar says, it's always wartime. Personal sacrifice is always called for. It is selfish and cowardly to live otherwise.

The book runs back and forth between extended descriptions of the lives of individual do-gooders and chapters discussing the philosophy and ethics involved in do-gooders in general. The pacing is good, the stories readable. I just don't know what to make of all this. It's a "huh. that's interesting" book for me, but I don't know what I'm going to do with that knowledge now. As MacFarquhar concludes, we can't all live like the extreme do-gooders she describes, but the world is a better place with them. I think I can agree with her on that. But it doesn't make me want to be a do-gooder, nor to encourage others to be. There's a lot of pain in here. As a whole, these do-gooders are not happy. But they do do good.

I got a free copy of this from First to Read.